Dear Friends,

Thanks again for supporting my book project, Janaína! After 8,674 miles and 11 days in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, I’m back in Harlem. It was a beautiful, productive trip. Here’s a little about my experiences and how they will help shape the novel. Below the bulleted summary is a more in-depth (unedited) reflection. Hope you enjoy!

What I did:

· Met and interviewed five sisters and a brother in their teens/twenties who live (and/or work) on the street. Their stories devastated and inspired me. I came away with a deeper understanding of the contradictions and depth of young people living this reality; the blurred lines of autonomy/dependency, dignity/shame, courage/terror. Loneliness, numbness. Tenderness. Despair and surprising faith.

· Connected with three agencies serving the city’s most vulnerable youth: CRIA (prevention/education through the arts), CAPS (substance abuse, family counseling and medical services) and FUNDAC (engages youth in the juvenile/criminal justice system). This was helpful for a vision of the institutional response to Bahia’s most vulnerable children, and gave me some ideas for fleshing out characters/ programs/places that are part of Dia’s world. (Dia and Mia are the twin protagonists in Janaína).

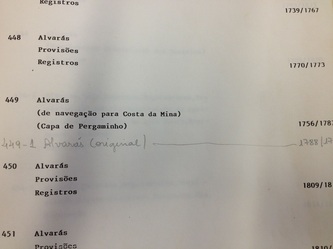

· Visited the Archivo Público, a state library holding historic records dating from Bahia’s colonial period. It was amazing to touch history, holding documents that some ancient hand scripted hundreds of years ago. Some items that caught my interest: a record of a 1756 journey to the “Costa de Mina" (modern day Gulf of Guinea). One of the most famous ports there was in São Jorge da Mina (Elmina Castle). I have photos/stories of my twin in this Ghanaian slave dungeon. My time in the archives was profound, more than I’d expected from a crumbling, colonial library.

· Attended a university lecture about Brazil’s mass deportations of enslaved and free Africans in the1830’s following one of Brazil’s largest Black uprisings, the Revolta dos Malês).

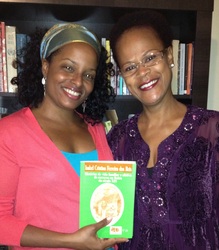

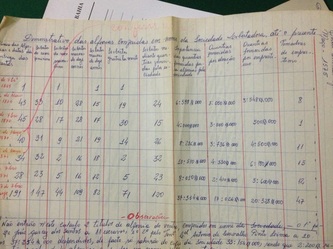

· Dialogued with one of Bahia’s leading historians (Dr. Isabel Cristina Ferreira dos Reis) on the Afro-Brazilian family during slavery and accessed her personal archives (over 8 handwritten volumes that hold the closest equivalent to our US slave narratives: testimonies/accounts of enslaved and free Africans during criminal and civil court cases). This one of the most illuminating parts of my trip and helped me understand what life was like for families that fought to reclaim children who were born free but kidnapped into slavery; women who committed suicide/infanticide in the ocean and using mill equipment; an African swindler who tricked a pair of sisters out of hard-earned money meant to purchase “alforria” (emancipation) with the promise of romance and marriage – and more. I was surprised that within the racist Brazilian legal system, there had been such in-depth contemplation of these cases, which provide rare windows into the intimate lives of enslaved/free Africans in Brazil. (My friend Isabel’s coming to the U.S. this winter and I’d love to help connect her with potential speaking engagements. Click here for details).

· Connected with leaders in the Afro-Brazilian movement against religious intolerance, who are fighting for the rights of candomblé practitioners to be free from persecution. Many people in my own spiritual community are on the frontlines of this national movement and this is a deeply personal issue for me. The communities continue to confront institutional discrimination, mob attacks, temple (terreiro) desecration, bullying of children/teens practicing African-based religions, and television/radio campaigns against a centuries-old religion which shaped so much of the national culture that Brazil prides itself on. One of the highlights of this trip was a personal screening of the documentary, “O Cuidar no Terreiro.” The short film features Afro-Brazilian religious leaders on core values in African-based religion; the religion’s role in preserving health/wellness in Afro-Brazilian communities; and the ongoing struggle to secure their constitutional right to freedom of religion. In a compelling scene (@20:30) a Black girl (about 12 years-old) talks about finding the strength to overcome being teased in school for her religion.

· Visited and photographed some of the neighborhoods where the Brazilian side of the novel will unfold. The sensory experience was so rich and helped me redraft several setting/ambient scenes in the book with more immediacy and emotion.

· Collaboratively determined how the Janaína fund will benefit Afro-Brazilian youth through a memory/memoir writing project in a low-income neighborhood known for the historic presence and activism of faith-based organizers from three candomblé terreiros. More on this soon!

· …. And yes, I was also able to get in two beach days, a barbecue, and visits with beloved friends. This is one thing I’ve always loved about Bahia: you can work hard and play hard too!

Thanks again for supporting my book project, Janaína! After 8,674 miles and 11 days in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, I’m back in Harlem. It was a beautiful, productive trip. Here’s a little about my experiences and how they will help shape the novel. Below the bulleted summary is a more in-depth (unedited) reflection. Hope you enjoy!

What I did:

· Met and interviewed five sisters and a brother in their teens/twenties who live (and/or work) on the street. Their stories devastated and inspired me. I came away with a deeper understanding of the contradictions and depth of young people living this reality; the blurred lines of autonomy/dependency, dignity/shame, courage/terror. Loneliness, numbness. Tenderness. Despair and surprising faith.

· Connected with three agencies serving the city’s most vulnerable youth: CRIA (prevention/education through the arts), CAPS (substance abuse, family counseling and medical services) and FUNDAC (engages youth in the juvenile/criminal justice system). This was helpful for a vision of the institutional response to Bahia’s most vulnerable children, and gave me some ideas for fleshing out characters/ programs/places that are part of Dia’s world. (Dia and Mia are the twin protagonists in Janaína).

· Visited the Archivo Público, a state library holding historic records dating from Bahia’s colonial period. It was amazing to touch history, holding documents that some ancient hand scripted hundreds of years ago. Some items that caught my interest: a record of a 1756 journey to the “Costa de Mina" (modern day Gulf of Guinea). One of the most famous ports there was in São Jorge da Mina (Elmina Castle). I have photos/stories of my twin in this Ghanaian slave dungeon. My time in the archives was profound, more than I’d expected from a crumbling, colonial library.

· Attended a university lecture about Brazil’s mass deportations of enslaved and free Africans in the1830’s following one of Brazil’s largest Black uprisings, the Revolta dos Malês).

· Dialogued with one of Bahia’s leading historians (Dr. Isabel Cristina Ferreira dos Reis) on the Afro-Brazilian family during slavery and accessed her personal archives (over 8 handwritten volumes that hold the closest equivalent to our US slave narratives: testimonies/accounts of enslaved and free Africans during criminal and civil court cases). This one of the most illuminating parts of my trip and helped me understand what life was like for families that fought to reclaim children who were born free but kidnapped into slavery; women who committed suicide/infanticide in the ocean and using mill equipment; an African swindler who tricked a pair of sisters out of hard-earned money meant to purchase “alforria” (emancipation) with the promise of romance and marriage – and more. I was surprised that within the racist Brazilian legal system, there had been such in-depth contemplation of these cases, which provide rare windows into the intimate lives of enslaved/free Africans in Brazil. (My friend Isabel’s coming to the U.S. this winter and I’d love to help connect her with potential speaking engagements. Click here for details).

· Connected with leaders in the Afro-Brazilian movement against religious intolerance, who are fighting for the rights of candomblé practitioners to be free from persecution. Many people in my own spiritual community are on the frontlines of this national movement and this is a deeply personal issue for me. The communities continue to confront institutional discrimination, mob attacks, temple (terreiro) desecration, bullying of children/teens practicing African-based religions, and television/radio campaigns against a centuries-old religion which shaped so much of the national culture that Brazil prides itself on. One of the highlights of this trip was a personal screening of the documentary, “O Cuidar no Terreiro.” The short film features Afro-Brazilian religious leaders on core values in African-based religion; the religion’s role in preserving health/wellness in Afro-Brazilian communities; and the ongoing struggle to secure their constitutional right to freedom of religion. In a compelling scene (@20:30) a Black girl (about 12 years-old) talks about finding the strength to overcome being teased in school for her religion.

· Visited and photographed some of the neighborhoods where the Brazilian side of the novel will unfold. The sensory experience was so rich and helped me redraft several setting/ambient scenes in the book with more immediacy and emotion.

· Collaboratively determined how the Janaína fund will benefit Afro-Brazilian youth through a memory/memoir writing project in a low-income neighborhood known for the historic presence and activism of faith-based organizers from three candomblé terreiros. More on this soon!

· …. And yes, I was also able to get in two beach days, a barbecue, and visits with beloved friends. This is one thing I’ve always loved about Bahia: you can work hard and play hard too!

Here are some reflections on what I experienced. Hope you enjoy!

1. The Invisible Ones

Salvador is a city that grabs you by the ear, nose, gut, heart and soul. It’s alluring. Intense. Music spills from windowsills, blares from vendors’ coffee carts, street corners. The nutty scent of dendê (African palm) oil thickens the humid air as brown women in white lace (baianas) deep fry acarajé (bean cakes) for rush-hour crowds. Lurching busses broadcast the city’s unofficial creed in white block letters: AXÉ. The city engages all six of your senses. Its streets pulse with energy: a capricious mix of exuberance and misery, sensuality and spirituality, destitution and decadence. Navigating the city’s cobble-stoned streets last week, I had an eerie feeling that something in that vibrant ecosystem had changed dramatically. Something – someone– was missing.

Within two days, I realized what it was: the meninos da rua (street children) have nearly disappeared from the corners, the historic Pelourinho area, Barra beachfront neighborhood, Piedade church front and other areas. These are neighborhoods where in the course of a ten-minute walk though these streets (only a couple of years ago), I’d encounter dozens of children and be approached by at least two or three. Now, they seem to have been replaced by a noticeably thicker police presence, blue and beige clad officers with hipfuls of billy bats, mace, revolvers and in some areas, machine guns. Cops – and hordes of stray dogs. Salvador’s people ambled easily around them, a river of vibrant color, language lilting like song. It felt like the twilight zone to me: something in the landscape had changed drastically, but life here seemed to be going on as usual.

Contemplating this shift, I hoped that with Brazil’s emerging superpower status, children who’d lived on the street were being better cared for somehow, routed back into schools and programs to keep them off the streets. And then my less naïve side feared another possibility I didn’t want to contemplate, though has been known to occur in Brazil: that the children were being exterminated.

Over the next few days, through conversations with moradores de rua, local leaders, youth agencies, and even some city officials, I received a range of explanations. The most common: that the children were being picked up and bussed to shelters in the “periferia” (outlying poor neighborhoods). Some mentioned the kids were being jailed for crack use and traffiking. Others said that the state was providing programs that helped stem the flow of families and young people from the interior (rural areas) by paying a stipend to keep their children in school. Still others said they believed that the children were being executed. The truth is somewhere in the range of these and beyond the scope of what I could explore. Still, this reality haunts me. So do the stories of the young people I met.

I will never forget “Sueli.” We connected as I was leaving Pelourinho, (a neighborhood named for its infamous slave pillory). A gangly teen girl in a floral halter top and leopard print short-shorts, Sueli’s skin was a canvas of scars, tattoos and open sores. A tight belly bulged beneath her blouse. Her eyes glinted with bravado, guile. When I asked how to spell her name, Sueli grabbed my spiral notebook and pen to write it herself, in careful, ornate cursive. I asked her about her tattoos, including a long cursive brand running elbow to wrist. “It’s my mother’s name,” she beamed. “Do you want to see my others?” Sueli gestured to her back where she’d tatted a huge scorpion. When I wondered whether she pregnant, Sueli laughed too quickly, then rested her eyes on the sidewalk, “não, é vermin.” (“No, its worms/disease.”) She told me about her struggles with drugs, being treated for her addiction, and staying some nights with her family in a neighborhood in the periferia. “I don’t stay on the street all the time,” she declared proudly. When I asked, “what do you dream of now?” Sueli chuckled, lengthened her spine, and squared her shoulders.

“I want to be a policeman and take these people off the streets….” she paused, stopping to stare at someone behind me. I held my breath, wondering whether she was about to refer to the vanishing streetkids, but she continued “…and put them in an enormous, beautiful home.”

“And you would be “a dona da casa (the woman/owner of the house?)” I asked.

“No, we’d all own it together. It would be all of ours.”

Sueli (not her real name) and I chatted a little longer about the daily pull of hunger, her daily routines, her family, removals of people from the streets. She also gave me the names of other programs I could look at and told me where to find more moradores da rua to talk to.

What struck me, on the bus ride home as I opened my notebook to her signature and the smudge of dirt/food beside it, was the care Sueli put into writing her name. Her eager, perfect penmanship, made me understand that this brazen, bruised young woman was once somebody’s baby. Someone had taught her, perhaps with faith in some bright future, how to write deliberately, beautifully, clearly. At some point in her life, Sueli been simply a little girl learning. Somebody’s baby girl. Imagining the short stretch of life between mastering her signature and smoking crack gave me chills. Made me wonder about the personal choices, family dynamics, depression and oppression that could have led her there. Lots for a heart to hold.

With few exceptions, the moradores da rua I spoke with mentioned their mothers within seconds of our conversation. Tattoos of mother’s names were traits just as common as blackened, calloused feet and scarred skin. I came upon a dreadlocked brother named João, while he was devouring a bagful of dripping oranges like a greedy lover. He barely came up for air during our conversation. He was recovering from an addiction, he explained, and had been on the streets since he was 10 years old. In barely intelligible Portuguese, João grieved openly for the shame he felt he caused his mother, who’s raising his son and still waiting for him to come back home for good. João repeated her name to me, almost as mantra, prayer. Raiumunda dos Santos. Raiumunda dos Santos. Raiumunda dos Santos. More than his name, he wanted to make sure I remembered the name of his mother.

Another common theme from the people I encountered on the street: finding permanent, stable work so they could get off the streets. One young sister who rocked a tiny ponytail and red flip-flops, stopped me to show her wares. On her hip, she hoisted a bucket full of red pens and tiny pencil sharpeners. “By the time I sell all of these, all day, I will only have made R$7 (US$2.30),” she lamented. Her dream, echoed in the dreams expressed by other young women I met, was to find a stable job like a “lavandeira” (a laundry woman) so she wouldn’t have to constantly hustle for new sources of income. Not surprisingly, domestic work is still the most common employment for Afro-Brazilian women to this day.

The question of work, because it was loomed so large in their longing, will be now become a bigger theme within Dia’s story (the Brazilian twin in the novel).

Among other issues facing the most vulnerable Black girls and young women: violence, abysmal self-esteem, sex trafficking, drugs, poverty, and AIDS. Issues these young women navigate on a daily basis. This from the young people themselves, statistical research and from staff in the agencies I visited this trip.

[Just for contrast – and to present another end of the spectrum – there is a growing, though small, sub-section of Black girls thriving in Brazil. These are children of the emerging Black middle class, including a dear friend’s daughter, a well-educated pre-teen who is already plotting step by step, how she might become Brazil’s first Black female Supreme Court Justice. I want to be careful to emphasize Black girls are not one homogenous category in Brazil, through poverty, violence and access to quality education are core issues for the majority.

2. History Demands its Place

After a decade, I know better than to arrive in Salvador with a handful of plans. My early Fulbright days, when I hustled to lock in meetings weeks in advance only to reschedule or sit waiting hours after the appointed time, taught me better. It’s a dance and you are rarely the lead partner. A certain alchemy is at work. It’s about serendipity and surrender. I’m not the only visitor to think of a person who suddenly appears on a street exactly when I want to see them – or finds some unarticulated need met before it can be vocalized. Here, I’ve found (sometimes the hard way) that you cannot force your way or plot your choice course. Yet, if you allow things to unfold naturally, the most amazing things often happen.

This was the case with my historical research. On two personal visits with a renowned priestess and with another prominent healer/activist in the candomblé tradition, I was unexpectedly treated to archives of photos from the 1930’s- 1940’s of historic terreiro (temple) grounds and community elders. I reverently witnessed the unfolding of a life in photos of a remarkable woman whose memoir encompasses some of the most significant turning points in Afro-Brazilian history. I was also honored to visit a family shrine that held ritual objects dating back generations. These were such rare and completely unexpected blessings, especially considering that neither of the visits was originally “intended” to be about history/research.

An outing for drinks with a longtime friend yielded an invite to a university lecture on the mass repatriation of enslaved and free Africans from Brazil to Benin between the 1830’s to 1870’s, following the Revolta dos Malês. After one of Brazil’s largest Black uprisings, the Brazilian government deported over 200 Blacks, many of whom had not even been part of the rebellion. A number of free Blacks with substantial wealth also decided to take the journey to escape the violently racist Brazilian society. The historian’s slide presentation began with an evocative photo: Black women and men (some with a bearing of dignity and others, resignation) aboard a ship about to depart for Benin. Generations later, many Benin/Togo descendents can still trace their lineages back to these Brazilian ancestors. Learning about this mass exodus to Benin has added another layer to my queries about the original Ojarô twins (twins that survived the Middle Passage to Brazil and inspired my book) and new curiosities about movement/migration between Africa and Brazil. Still, much more to learn…

Yet another unplanned blessing on the history front, one that kept me up several late nights: Studying colonial court records (the closest thing to slave narratives in Brazil). I had not planned it in advance, but ending up staying at the home of a good friend, one of the state’s leading historians, Isabel Cristina Reis, who’s written a book on the Afro-Brazilian family during slavery. She allowed me to sift through volumes of first-hand historical documents that she’d copied meticulously during the years of her dissertation research.

There were many gut-wrenching stories of suicide and infanticide, such as this one: March 1847. Slave woman attempts suicide/infanticide with her three children in the ocean. Two survive and became wards of the state. The mother is sentenced to prison after release from a sanitarium. Her motive, as expressed in a letter from the hospital administrator: To free herself and her family from the abuse of their Senhor (slavemaster). This was correspondence from the “subdelegado da Conceicao da Praia to the Chefe da Policia.”

Other common cases involved slaves whose liberation had been achieved through painstaking (often years-long savings) but was contested by masters who pocketed their money and refused their freedom, sometimes sending them to jail or back into slavery.

I also found cases of parents fighting to reclaim children who were supposed to have been born free after the “Lei do Ventro Livre,” passed in September 1871. The abolitionist law guaranteed freedom for all children born to slaves born after this date. A summary of two such cases:

- Raymundo da Sé, 9 years old, son of slave Maria dos Santos. He should have been born free but was separated and sold away from his mother back into slavery.

- Leopoldina, 16 years old. She was a child of the couple Ritta (cabra) and Telles (pardo). When she became of age and wanted to leave the house to start her own life, the family was surprised to learn that she was not free to go. Though she he was born free to slaves and after her birth, she was reclaimed by the slave-owner because of she was part of an alleged inheritance to be paid.

At Isabel’s I read through dozens of court records and old Portuguese letters, more than I can summarize here. These narratives will inform the plot line and back-story for main characters in Janaína.

3. The Ocean’s Embrace

The axé (spiritual energy) of the Atlantic carried me and surrounded me on this trip. The ocean has always been sacred to me, a place of bliss and play. It was omnipresent in almost every aspect of my eleven days. During the first week, I was blessed to write and sleep to the rhythm of waves greeting the shore and I awakened each morning to a dramatic oceanfront view. Nothing like it!

At the beach in Stella Maris, once home to a quilombo (maroon slave community), visions of Janaína came to me in waves, clear as a movie. The water was deep and serene. I was able to swim way out to a fleet of empty fishing boats and float on my back uninterrupted, watching the breeze tease the clouds. In the freedom of that water, I imagined the importance of the sea for Dia: Welcoming arms that do not discriminate, cleanse her spirit, heal her scars, bear the weight of memory and longing. And on the lighter side, I got an idea on expanding a scene where Dia and Mia race against each other, one of the first of many competitions between them.

In my research, the sea was ubiquitous: A refuge for the souls of children whose mothers brought them to the ocean to set them permanently free from slavery. Bearer of middle passage ships that landed here with human cargo – and ships repatriating Afro-Brazilians to Benin and beyond. The ocean is revered in Salvador’s annual offerings to the “Great Mother” during the Festa de Iemanjá, in which thousands come to bring offerings to the orixá Iemanjá, who represents oceans, motherhood, creativity, and is often syncreticized with Mother Mary. Iemanjá/Mary is often considered Brazil’s patron saint.

Riding the bus up and down the gorgeous “orla,” coast, I’d watch throngs of brown and tan folks at the beach, families splashing with chubby babies, lovers entwined, a tangle of limbs and thongs, soccer players in slick shorts, soda vendors, and folks scavenging the sand for bottles to recycle and leftover food. Sometimes, just stretches of empty beach, palm trees and ribbons of sparkling sea.

And again, thousands of miles beneath my tiny window on the flight home, there is the ocean in bright turquoise and white dress. I take note of her on every crossing from Harlem to Bahia and back. Even when the 10 hour + journey drags, I imagine the months it took centuries ago for my ancestors to make their own trans-Atlantic journeys. And I can’t help but admire the twin girls who made that arduous journey at nine years old.

How will all of this shape my novel, Janaína?

Given the depth of all I experienced, I’m still processing what this means for the book. I’ll be writing my way to the answer. Here are some initial thoughts.

History loomed so large on this trip, much more than I’d planned. It was almost as though Bahia demanded I honor the past/place that birthed my main characters. The colonial archives, court records, old photographs, family lineages, and stories I saw/received have given me a richer texture for ancestor dream sequences that thread through the book. I may also do more of more intentional ancestral story line in parallel with main characters Dia and Mia (the modern-day twins).

This unexpected insistence/emergence of history also made me honor just how old a city Salvador is (464), how it has evolved and how it is almost a character unto itself. Established in 1549, by Thomé de Souza, the first Governor-General of Brazil, Salvador was Brazil’s first capital and is one of the oldest cities in the Americas. It was a vital center for the sugar and slave trade. Today it is the third largest city in Brazil – and the state is still home to the largest population of African-descended people outside of Nigeria.

Another influence on the book: As I read accounts of orphaned/kidnapped slave children and talked to young people in the streets now, I felt strong parallels in roots/uprooting of Black children during slavery and on the streets today. Echoes of trauma, violence and longing for family reverberated back and forth across the testimonies, centuries apart. Mother love, an anchor then and now. This was already a core theme in Janaína and my trip confirmed its significance.

Related to the mother/history theme: o mar (the ocean) or Great Mother, for all the reasons I mentioned earlier was so instructive during this trip. In many ways, She holds my story, the ancestors’ stories and the story of Janaína…

I’m contemplating faith as a source of healing, endurance and mystery. The contradictions of freedom and confinement within organized religion… community as a source of healing and wounding, power and vulnerability. Wordless now as I think on this. Will allow the novel to speak for me here.

Young people yearning for stable work. Since this question loomed so large in their longing, it will now figure more directly into Dia’s story.

To my ear, Bahian Portuguese is one of the most beautiful languages in the world. I’m still marinating on how to represent the Portuguese in the book, so that is not lost in translation. So that the beauty and poetry of language here and the sense of song that is transmitted. I also have more ideas on how to convey Mia operating in a land where she no longer remembers her mother tongue…and how she rebuilds a relationship with a sister who doesn’t speak her language.

And so much more….but this is running long so I’ll end here…

Writing on,

Lorelei

RSS Feed

RSS Feed